Historical Background

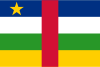

The Central African Republic (CAR) is landlocked with a centuries-old tradition of peaceful co-existence between Christians and Muslims. Since it was granted independence from its French colonial master in 1960, the country has been plagued with sectarian violence, with six successive coups d’état, the most recent in 2013, which has left the country in shambles. The country has not fully recovered ever since. The signing of the political peace agreement in February 2019 was a move in the right direction to bring about sustainable peace (United Nations, 2019). The violence in the CAR is championed predominantly by two factions – the Muslim Seleka militia and the Christian anti-Balaka militia (ibid). As a percentage of the total population, displacement is a major concern in the CAR, as one person in five is displaced in the country (OCHA, 2023b). In 2014, during a brief visit to the country, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, António Guterres, described the situation in the CAR as “a humanitarian catastrophe of unspeakable proportions” (United Nations, 2014).

A quarter of the population of the country has been displaced since violence spiralled in 2013 (Migration Data Portal, 2023). The idea of a constitutional review bringing about political stability and development is yet to be realised. Although there has been a constitutional review in 2023, the amendments did not translate into improved living conditions for the masses; instead, they concentrated on giving more powers to the president. For example, one of the clauses of the amendment increased the tenure of the president from five to seven years and abolished the presidential term limit (Africanews, 2023). The country’s political changes have been criticised by the opposition, calling it a design by the president to rule for life (ibid). Although parts of the country have experienced relative stability, the political situation is still fragile.

Due to the recurrent militia attacks, political instability, low economic drive, and multidimensional poverty, the CAR is not an attractive destination for migrants. However, because of its central position in Africa and the ongoing violence in the country, it remains a transit route to many migrants from the region and a host to refugees fleeing persecution from neighbouring countries.

Migration Policies

The Central African Republic is part of the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), which allows the free movement of its nationals within member states.

The government has not yet ratified the International Labour Organization’s convention on labour migration. The CAR is a signatory to both the 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (Geneva Convention) and the 1967 protocol and has ratified the 1969 Organisation of African Unity (OAU) Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa. The 1990 Constitution of the Central African Republic, as amended in 2023, indicates that ratified treaties are a higher source of authority than national laws. The 2007 Refugee Law, in principle, allows refugees to join the labour market and to use social services, hospitals, and educational facilities just like the country’s nationals. The CAR ratified the 1989 United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) and the 2009 African Union Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa (Kampala Convention).

With reference to smuggling and trafficking, the Central African Republic has ratified both the 2000 UN Protocol against the smuggling of migrants by land, sea, and air and the 2000 UN Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children. Article 151 of the penal code criminalises all instances of trafficking, and offenses can be punished with life imprisonment and hard labour. However, these legislative frameworks are seldom implemented.

In the absence of a single migration policy framework in the CAR, the constitution and its amendments remain the only legal framework that shapes migration policy in the country.

Governmental Institutions

The following government institutions oversee migration-related issues:

- The Ministry of Foreign Affairs, African Integration, and Central Africans Abroad is the main ministry in charge of immigration. It is also in charge of relations with the Central African diaspora.

- The Ministry of Interior and Public Security is in charge of immigration/emigration and the control of foreigners.

- The Ministry of Justice, Legal Reforms, Human Rights, and Keeper of the Seals is in charge of challenges pertaining to human trafficking.

- The National Refugee Commission (CNR), under the Ministry of the Interior, grants asylum in accordance with the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 protocol.

Internal Migration

Internal migration in the Central African Republic happens in forward and backward waves – or rural-urban and urban-rural movements. The capital city (Bangui), with its socio-economic infrastructure, urban lifestyle, and with the only university in the country, attracts migrants to the city. At the same time, hardship and unemployment are pushing people to return to rural areas where they can pursue a subsistence/agricultural lifestyle (International Organisation for Migration – IOM), 2014).

Data from the latest census indicates that unemployment in urban areas is more than three times higher than in rural areas, at 15.2% and 4.2% respectively (ibid). Significant numbers of people also migrate from both urban and rural areas toward the natural resource sector, with increased migration toward mines, tobacco plantations, and forestry (ibid). This implies that internal migration is mostly driven by economic opportunities. With the dense population of pastoral nomadic groups, rural-rural migration is also evident.

Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs)

Internal displacement in the Central African Republic is largely caused by conflict and violence mostly triggered by political tensions. As a result of the 27 December 2020 general elections, the country recorded its highest number of internally displaced persons (IDPs) since 2014 (UNICEF, 2021). An estimated 738,000 people, half of them children, were internally displaced across the country (ibid). However, these figures have experienced a steady decline. In December 2022, there were 515,700 internally displaced persons in the Central African Republic (UNHCR, 2023a), with these figures dropping to 488,861 in April 2023 (ReliefWeb, 2023). New displacements were triggered by armed conflicts between the Central African Armed Forces (FACA) and armed groups, particularly in the areas of Ombella, M’poko, Haut-mbomou, and Ouham (ibid). By the end of 2023, the number of people displaced because of conflict and violence dropped to 512,000 (IDMC, 2024). More recently, conflict and violence are still dominating the displacement space in the CAR. For example, attacks by armed men in the Ouham-Pende region caused the displacement of 6,000 people (OCHA, 2025).

Over and above conflict and violence, natural disasters also contribute to internal displacement, compounding the already precarious situation. According to Floodlist (2022), flooding affected 12 of the 17 prefectures in the country, displacing more than 600 people. The hardest hit areas were the Northern Vakaga prefecture, the capital Bangui, and the Ouham prefecture (ibid). Some of those who have been internally displaced are accommodated in settlements such as Pladama Ouaka and PK3, with humanitarian and development agencies and local authorities assisting occupants with accommodation, classrooms, markets, boreholes for potable water, and plots of farming land (OCHA, 2023c).

Immigration

The CAR is not an attractive destination for most migrants because of the recurrent political instability in the country. Although research has been done on forced displacement, very few studies have been done on people who voluntarily come into the country. According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), as cited by the Maastricht Graduate School of Governance (2017), migrants from Cameroon made up the largest share of the immigrant population in the CAR, followed by those from Chad, the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Republic of Congo, and France.

However, recent statistics indicate that the top five immigrant origin countries in the CAR are Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Chad, France, and South Sudan (UN DESA, 2025). The immigration stock in the CAR was at its peak in 2010 when it stood at 94,700. In 2015, it went down to 81,600 while it increased to 88,500 in 2020 and to 94,600 in 2024. The trend indicates a steady increase from 2015 to 2024. The recurrent political instability in the country, characterised by armed conflict and chronic insecurities, prevents it from leveraging its full economic potential and makes it an unattractive destination for most migrants.

Gender/Female Migration

Although there are recurrent armed insurgencies in the CAR, women, mostly from neighbouring countries, are still involved in cross-border trading as it remains a source of revenue to improve their livelihoods and that of their families. According to the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA, 2025), the share of female migrants in the CAR has been stable from 2010 to 2024.

The report states that, in 2010, there were 44,300 female migrants in the country, while in 2015, the number dropped slightly to 38,400 and increased slightly in 2020 and 2024 to 42,200 and 45,100 – representing 46.8% in 2010, 47.1% in 2015, 47.6% in 2020, and 47.6% in 2024 as a percentage of the immigrant population in the CAR (ibid). The insecurity levels in parts of the country increase the vulnerability of women to gender-based violence (GBV), thus limiting female migrants from coming into the country. Also, women traders are subject to extortion by border control officers.

Children

Although there is no specific data on the demographics of migrant children in the CAR, there is some general information on migrant children and the situation in which they find themselves. According to UN DESA (2025), in 2020, 23.6% of the immigrant population in the CAR were children below the age of 18.

The recurrent armed conflict between government forces and rebel groups in the CAR has had dire consequences for children, including migrant children. UNICEF warns that large-scale displacement exposes children, including migrant children, to the risk of grave child rights violations such as recruitment as combatants, porters and spies, and sexual exploitation by armed forces and rebel groups (UNICEF, 2021). According to the United Nations (2021), 370,000 children were internally displaced in the CAR because of increased tension between warring factions in the country before the December 2020 presidential elections. These tensions pose a major threat to the development of such children as it adversely affects access to necessities like health care, education, and food.

Refugees and Asylum Seekers

The CAR is mostly recognised as a refugee origin country and not a refugee destination country. Hence, the presence of refugees in the CAR is testament to the recurrent conflict in neighbouring countries. In March 2025, a total of 681,146 refugees from the CAR were hosted in countries such as Cameroon (284,170), the Democratic Republic of Congo (207,302), Chad (141,487), the Republic of Congo (35,355), Sudan (10,058), and South Sudan (2,774) (UNHCR, 2025a). At the same time, the CAR hosted 51,349 refugees from countries such as Sudan (35,935), the Democratic Republic of Congo (6,501), Chad (5,002), South Sudan (3,198), others (476), and 8,282 asylum seekers (UNHCR, 2025b).

By law, refugees in the country should know the outcome of their status within 30 days of submitting an application and being interviewed (Maastricht Graduate School of Governance, 2017). Upon recognition as a refugee in the CAR, the individual enjoys freedom of movement, access to the labour market, education, and health services (ibid). Although refugees have freedom of movement, the political tension and recurrent confrontation between armed forces and rebel movements constrain their movement as they prefer, for security reasons, to live in the seven refugee camps spread across the country (ibid).

Emigration

With 70% of its population living below the poverty line, the CAR is one of the poorest and most fragile countries in the world, despite its rich resource endowment (OCHA, 2023a). The multidimensional poverty in the country is one of the main drivers of emigration. For the past two decades, those leaving the country have increased exponentially. According to UN DESA (2025), in 2010, the number of emigrants stood at 228,500. In 2015, it increased to 666,100, in 2020 it went up to 794,400, and in 2024 it went up to 905,800. According to the World Bank (2023), in 2022, the net migration rate of the CAR stood at -17,463, indicating that more people had left the country than those coming into the country. Emigration is considered a survival mechanism, not only to mitigate against poverty but also against renewed hostilities between armed groups.

Labour Migration/Brain Drain

There is a lack of data on employment and work-related matters, disaggregated by national origin, that adequately reflects the situation of labour migrants in the country. Although the government of former president François Bozizé, who ruled from 2003 to 2013, facilitated the process of obtaining visas to the Central African Republic, the country’s political instability and economic uncertainty make it unattractive for labour migrants. These migrants mostly have a low level of education and migrate to the country for unskilled professional reasons (Maastricht Graduate School of Governance, 2017).

Although as a member state of the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) – which has as one of its objectives the progressive removal of barriers to the free movement of persons, goods, services, and capital and the right of establishment the absence of basic identification documents prevents migrants from gaining access to social security which they are entitled to by virtue of their employment (Thornberry, 2017). This is an example of the disjuncture between constitutional imperatives and the lived reality of migrants in the CAR. Recently, transhumant pastoralists have also been migrating seasonally with their livestock from Cameroon into the northwest of the country (Usongo & Moussa, 2021). They are predominantly Muslims.

Unauthorised Migration/Trafficking and Smuggling

In a country plagued with recurrent military coups and political instability, it is common knowledge that hideous activities like human smuggling and human trafficking are taking place. In the CAR, while human smuggling is not very common, human trafficking is more common. The CAR is ranked Tier 2 in the 2024 Trafficking in Persons (TIP) Report. Human trafficking in the country exploits domestic and foreign victims in the CAR and abroad – Cameroon, Chad, Nigeria, the Republic of Congo, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan, and South Sudan (US Department of State, 2024).

Perpetrators of human trafficking in the CAR include transient merchants, herders, and non-state armed groups who exploit children in domestic servitude, sex trafficking, forced labour in agriculture, artisanal gold, and diamond mines, shops, drinking establishments, street vending, forced marriages, and who forcefully recruit child soldiers (ibid). The government, to strengthen its fight against human trafficking, enacted Law 22015 in 2022, which includes the provision of victim protection and prevention efforts. To this effect, the government, in partnership with NGOs and international organisations, provides services such as shelter, necessities, medical care, and witness protection to victims of human trafficking. No prosecutions were made in the reporting year 2023.

However, in 2024, the government prosecuted two suspects, and no convictions were made (ibid). The government identified nine trafficked victims (four sex trafficking and five forced labour victims). Although child trafficking remains a serious concern in the country, particularly with the activities of the militia groups, the government in 2024 did not report on child victims of human trafficking. However, since the conflict started in 2012, armed groups have recruited more than 17,000 child soldiers, mostly from Vakaga, Haute-Kotto, Haute-Mbomou, Nana-Grebizi, Nana-Mambere, and Basse-Kotto (US Department of State, 2021). Many militias and armed groups continue to recruit child soldiers and abduct children for child labour (US Department of State, 2024). The presence of militia activities in the country and corruption within the ranks of certain government officials hamper the ability of the state and other stakeholders to identify and assist victims of human trafficking and prosecute perpetrators.

Remittances

The absence of data makes it difficult to determine the current remittance landscape in the CAR. According to the World Bank (2023), the CAR experienced remittance flow as a percentage of the gross domestic product (GDP) only between 1977 and 1978, when it stood at 0.4% and 0.2%, respectively, as a percentage of GDP. Since then, the value has been zero. This is partly because of the absence of data, as explained above.

Returns and returnees

Although the political situation in the CAR remains fragile, there is relative stability in most parts of the country. This has facilitated the return of many Central Africans who have been displaced for more than a decade, particularly in 2013 with the outbreak of the violent conflict that saw more than 200,000 people displaced (UNHCR, 2022). Since 2017, when voluntary return started, the UNHCR has facilitated the return of an estimated 49,000 refugees to the CAR, mainly from Cameroon, the Republic of Congo, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (UNHCR, 2025b).

Although voluntary return was halted by the Covid-19 outbreak and fresh conflict as a result of the December 2020 elections, the return process in the DRC resumed in October 2021 and saw the return of over 5,500 Central African refugees from the Inke, Mole and Boyabu camps in the DRC’s North and Ubangi provinces (UNHCR, 2022). Also, as of May 2023, a total of 3,397 Central African returnees – mostly women and children (87%) from Sudan – are living with host families and or in settlements in Am-Dafock, CAR (OCHA, 2023b). Furthermore, the UNHCR supported an estimated 4,174 refugees repatriated predominantly from the DRC and Cameroon, and 10,300 returnees from Sudan and Chad (UNHCR, 2024). The UNHCR supports some returnees with cash to cover travel expenses and immediate needs upon arrival in the CAR (ibid). The process of facilitating and supporting returnees will continue as there is renewed interest in people wishing to go back home, according to a UNHCR survey conducted in eastern Cameroon, which indicated that more than 80,000 Central African refugees intend to go back home in 2025 (UNHCR, 2025c).

Some internally displaced people are also returning to their communities. In 2023, an estimated 343,500 internally displaced people returned to their communities with the assistance of the UNHCR (UNHCR, 2024). In 2022, the UNHCR facilitated the return of 800 people to their communities of origin from PK3 – a camp that hosts 33,000 displaced people (UNHCR, 2023). Some of the returnees benefitted from the UNHCR’s assistance packages, which include the provision of shelter and shelter kits for the building and maintenance of shelters (UNHCR, 2024). The challenges confronting returnees include acute food shortages and the high prices of necessities triggered by insecurity in the border region between Sudan and the CAR (Sudan is a major supplier of necessities to several towns in the CAR) (OCHA, 2023d). Also, the recurrent political tension in the CAR does not guarantee a sustainable stay for the returnees in their communities, as they can be displaced again.

International and civil society organizations

The following organisations provide migrant-related services in the CAR:

- International Organization for Migration: The IOM maintains a strong presence in the Central African Republic. The IOM, in collaboration with local partners and the government of the CAR, provides support for the stabilisation and immediate recovery of communities at risk, helps to strengthen inter-community dialogue and non-violent conflict resolution, and increases national response and awareness-raising capacities to combat human trafficking and other forms of exploitation.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees: The UNHCR provides life-saving protection and assistance, distributes basic relief items to internally displaced persons (IDPs), returnees, and refugees, and sets up new community shelters to accommodate the growing numbers of IDPs and returnees.

- International Committee of the Red Cross and International Rescue Committee: The ICRC and IRC provide medical care, water and sanitation services, and protection for vulnerable women, girls, and IDPs.

- Danish Refugee Council: The DRC implements a variety of programmes designed to support communities transitioning from emergency to early recovery, including protection, livelihood, education, rehabilitation, and economic recovery programmes.

- Norwegian Refugee Council: The NRC provides humanitarian assistance to IDPs, refugees, and communities. This includes support regarding education, information counselling and legal assistance, livelihood and food security, shelter and settlements, water, sanitation, and hygiene.

- Oxfam: This UK-based organisation supports civil society organisations with their development and has an advocacy component to protect and defend the rights of the most vulnerable, including refugees and IDPs.

- World Food Programme: The UN’s WFP helps food-insecure people, including refugees and IDPs, to meet their basic food and nutrition requirements.

Africanews. 2023. Central African Republic’s top court confirms constitutional referendum results. Retrieved from: https://www.africanews.com/2023/08/22/central-african-republics-top-court-confirms-constitutional-referendum-results//

Floodlist. 2022. Central African Republic – floods in 12 prefectures leaves thousands displaced, 11 dead. Retrieved from: https://floodlist.com/africa/central-african-republic-floods-june-october-2022

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2014. Migration dimension of the crisis in the Central African Republic: Short, medium and long-term consideration. Retrieved from: https://www.iom.int/files/live/sites/iom/files/Country/docs/Migration-Dimensions-of-the-Crisis-in-CAR.pdf

Maastricht Graduate School of Governance. 2017. Central African Republic – Migration profile: Study of migration routes in West and Central Africa. Maastricht University. Retrieved from: https://www.merit.unu.edu/publications/uploads/1518183851.pdf

Migration Data Portal. 2023. Migration data in Middle Africa. Retrieved from: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/regional-data-overview/middle-africa

Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). 2023a. Central African Republic: Situation Report, 13 October 2023. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/central-african-republic/central-african-republic-situation-report-13-oct-2023

Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). 2023b. Central African Republic: Situation Report, 30 May 2023. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/central-african-republic/central-african-republic-situation-report-30-may-2023

Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). 2023c. Central African Republic: Situation Report, 7 June 2023. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/central-african-republic/central-african-republic-situation-report-7-june-2023

Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). 2023d. Central African Republic. Situation Report, 29 June 2023. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/central-african-republic/central-african-republic-situation-report-29-june-2023

ReliefWeb. 2023. RCA: Rapport narratif CMP. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/central-african-republic/rca-rapport-narratif-cmp-avril-2023

Thornberry, F. 2017. Working conditions of indigenous women and men in Central Africa: An analysis based on available evidence. International Labour Office, Working Paper No. 2/2027. Retrieved from: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---ilo_aids/documents/publication/wcms_613855.pdf

UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA). Central African Republic. Retrieved from: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2022. Hopeful Central African refugees return home from DR Congo. Retrieved from: https://www.unhcr.org/news/stories/hopeful-central-african-refugees-return-home-dr-congo

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2023a. Central African Republic situation. Retrieved from: https://reporting.unhcr.org/operational/situations/central-african-republic-situation#:~:text=As%20of%20December%202022%2C%20515%2C700,and%20South%20Sudan%20(2%2C300)

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2023b. Regional response – Central African Republic situation. Retrieved from: https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/car

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2023c. After conflict, the displaced of Central African Republic dream of going home. Retrieved from: https://www.unhcr.org/news/after-conflict-displaced-central-african-republic-dream-going-home

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2024. Central Africa Republic situation. Retrieved from: https://reporting.unhcr.org/operational/situations/central-african-republic-situation

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2025a. Refugees and Asylum-Seekers from the Central African Republic. https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/car

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2025b. Central African Republic. Retrieved from: https://data.unhcr.org/en/country/caf

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2025c. Central African Republic Situation. Retrieved from: https://reporting.unhcr.org/operational/situations/central-african-republic-situation

UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF). 2021. Central African Republic: Nearly 370,000 children now internally displaced amidst ongoing violence – highest number since 2014. Retrieved from: https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/central-african-republic-nearly-370000-children-now-internally-displaced-amidst

United Nations. 2014. Secretary-General’s remark to the Security Council on “Cooperation between UN and Regional and Sub-regional organisations” (European Union). Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/statement/2014-02-14/secretary-generals-remarks-security-council-cooperation-between-un

United Nations. 2019. Central African Republic: UN chief hails signing of new peace agreement. Retrieved from: https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/02/1032091

United Nations. 2021. 370,000 children displaced in Central African Republic; highest level since 2014. Retrieved from: https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/04/1090812#

United Nations. 2023. As situation remains fragile in Central African Republic, local elections crucial for broadening political space, special representative tells security council. Retrieved from: https://press.un.org/en/2023/sc15328.doc.htm

US Department of State. 2022. Trafficking in Persons Report: Central African Republic. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2022-trafficking-in-persons-report/central-african-republic/

US Department of State. 2024. Trafficking in Persons Report: Central African Republic. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2024-trafficking-in-persons-report/central-african-republic/

Usongo, L. & Moussa, B. 2021. The dynamics and impacts of transhumance and neo-pastoralism on biodiversity, local communities and security: Congo Bason. German Facilitation to the Congo Basin Forest Partnership. Retrieved from: https://pfbc-cbfp.org/fileadmin/user_upload/pfbc-cbfp/Ressources/Etudes_du_PFBC/2021_CBFP_Transhumance___Neo-pastoralism_in_the_Congo_Basin_Report_eng.pdf

World Bank. 2023. Personal remittances, received (% of GDP) – Central African Republic. Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.TRF.PWKR.DT.GD.ZS?locations=CF