Historical Background

Historical Background

Malawi is largely characterized by a historical context that saw a great deal of outward flow of labour from colonial Malawi (Nyasaland) to nearby mineral-rich countries such as South Africa, colonial Zimbabwe (Rhodesia), and colonial Zambia. It was in South Africa and Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) that many Malawian labourers worked in mines, typically under the ploy of deferred payment, which was a concept that enabled the usage of Malawian labour for payment only upon a labourers return to Malawi (Dinkelman and Mariotti, 2016). Following a period of decline in migration to work in the mines in the 1980s, Malawians continued to emigrate to South Africa to seek various jobs in the growing informal sector and for trade purposes (Banda, 2017).

However, the inward flow of labour in Nyasaland (Malawi) was known to have been largely driven by an entry of Alomwe migrant workers from Portuguese East Africa (Mozambique) through the late 19th century and first half of the 20th century during a period in which plantations were said to be in significant demand for labour (Chirwa, 1994). The economy of Nyasaland thrived on the backs of socially vulnerable workers which was a group made up in part by immigrants. Mozambican labour migration into Nyasaland occurred in different phases. One phase developed migration through the establishment of contact between the Church of Scotland and locals in the country. The next phase was driven by a change in internal sources of labour due to external recruiting, and the final phase occurred in response to the growth of tea plantations in Nyasaland, and Mozambique’s proximity to the near-border plantations as well as the welcoming of external recruiters in Nyasaland (Chirwa, 1994). Employers at this time usually welcomed external labour from Mozambique as it was easier for them to exploit the labour and keep themselves competitive against external recruiters that drained much of the internal labour in the country.

Historically, Nyasaland’s labour migration can be understood through the lens of overwhelming competition for specific industries against other industries as well as against external recruiters in relation to internal labour. Efforts to curb the outflow of internal labour have been exemplified through government agreements to nullify external recruitment in the late 20th century between Malawi and South Africa (Boeder, 1984).

Migration Policies

Migration Policies

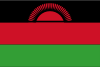

The primary legislation governing immigration-related issues in Malawi is the Malawi Immigration Act of 1964, with its subsequent amendments up to 1988. The Act lays out the legal prescript governing general immigration and emigration, issuance of residence, and other permits (IOM, 2014). Concerning refugees and asylum seekers, the Malawi Refugee Act of 1989 established a refugee committee that will, inter alia, receive and hear applications for refugee status and may grant or deny the grant of refugee status.

Timeline of Migration Policies in Malawi. Source: SIHMA

At the regional level, Malawi is a member of the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC), which has as one of its main objectives, to facilitate the movement of people within the region and ultimately remove obstacles to the free movement of goods, services, capital, and labour. Malawi is also a member of the Common Market for East and Southern Africa (COMESA) which adopted the protocol of the Free Movement of Persons, Labour, Services, and the Rights of Establishment and Residence.

Malawi is a signatory to:

● The OAU Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa (ratified 1987)

● The UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, 1951 (ratified 1987)

● The UN Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, 1967 (ratified 1969)

● The UN Human Trafficking Protocol, 2000, (ratified 2012)

● The UN Migrant Smuggling Protocol, 2000 (ratified 2012)

● ILO Migration for Employment Convention (ratified 1965)

● ILO Migrant Worker Convention (ratified 1987)

● Convention of the Rights of the Child (ratified 1991)

● UN Migrant Workers Convention (ratified 1991)

● 2000 Human Trafficking and Migrant Smuggling Protocol (ratified 2005)

In 2018, the government of Malawi agreed to roll out the Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework (GRRF) under the New York Declaration of 2016 which will enhance the harmonious co-existence of refugees and asylum seekers with nationals (UNHCR, 2021). Despite its enrolment, the Malawian government is not implementing the five key pledges it made during the GRRF Summit to realize its goal of facilitating the integration of refugees and asylum seekers within communities through policy frameworks. This is evident in the March 2023 government directives which ordered the forceful return of all refugees and asylum seekers back to the Dzaleka refugee camp.

Governmental Institutions

Governmental Institutions

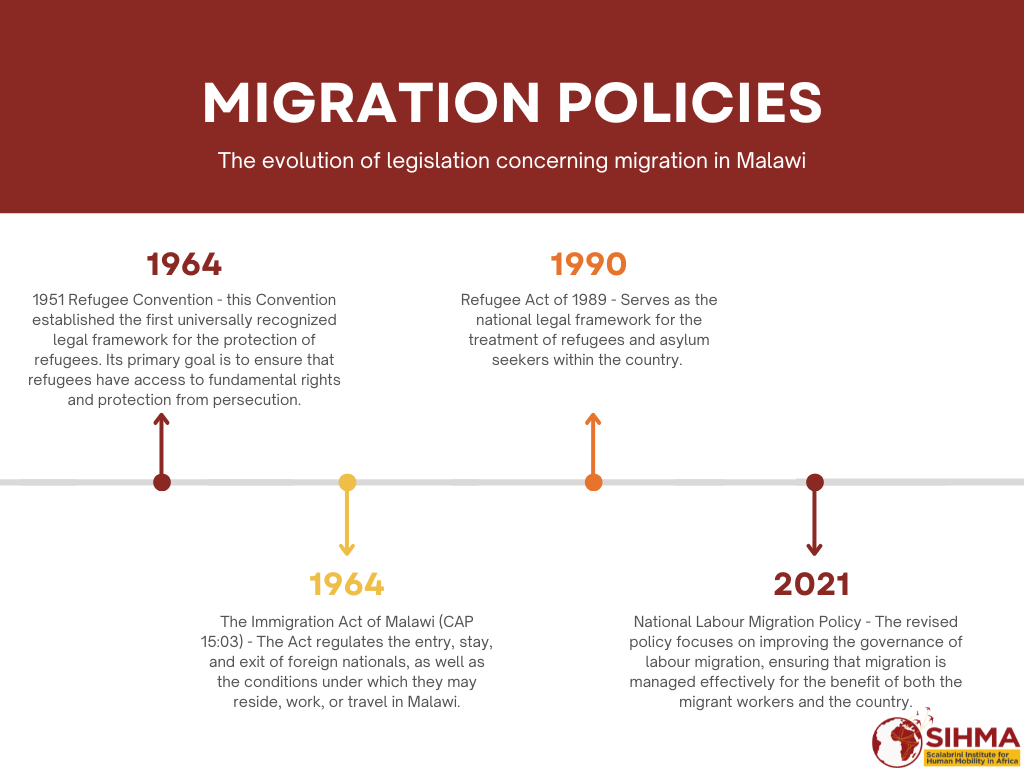

The frontline national departments involved in managing migrants, refugees, asylum seekers, and other categories of migrants in Malawi include the Ministry of Home Affairs, Immigration Department, Malawi Police Services, Prison Services, Ministry of Gender, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation.

Malawi's Government Structure. Source: SIHMA

Through the Ministry of Home Affairs, the Immigration Department provides services to the general public on border control, issuance of travel documents, residential and work permits, visas, and citizenship to eligible persons. The Malawi Police and Prison Services have records of migrants arrested and imprisoned for law infringement. The Ministry of Gender handles cases of minors who are separated, unaccompanied, smuggled, and vulnerable women migrants.

Internal Migration

Internal Migration

Malawi has experienced very little change in terms of its urbanization rate from 1987 – 2018. According to the most recent census conducted in 2018, the proportion of the national population living in urban areas increased marginally from 14.4% in 1998 to 15.3% in 2008, and 16% in 2018 (National Statistics Office, 2019). Although with a steady increase in the urban population volume in Malawi, infrastructural development in the country remains low. Ranked 169 out of 191 countries on the Human Development Index report of 2021, Malawi is considered one of the least urbanized countries in the world (UNDP, 2022). With low infrastructural development, rural residency is predominant, as most of the Malawian population (84%) reside in rural areas, and the bulk of rural migrants move into other rural areas (Chilunga, et al. 2019). Although 84% of Malawians live in rural areas, internal net rural-to-urban migration, predominantly for economic reasons, has been increasing steadily at 4.1% per annum (Ibid). Because of economic activities in the south, like large fisheries and fish farms in the Southern shores of Lake Malawi, and the massive agricultural targeted national investment policy launched by the national government, the southern district represents the most attractive destination for internal migrants (Ibid). However, internal migration is rising in the northern region (Ibid). Demographically, internal migrants in Malawi are distributed equally between men and women (Anglewicz, et al., 2019). While most men are moving for work, most women are likely to be moving for marriage. Anglewicz, et al. (2019) posit that because divorce, widowhood, and remarriage are common in Malawi, there is a growing number of marriage-related migration.

Internally Displaced Persons

Internally Displaced Persons

Data from 2019 show that 149 individuals in Malawi were internally displaced due to conflict and violence and from January - March of 2022, 190,429 individuals were displaced due to flooding in multiple districts in the southern regions of the country (IDMC, 2022).

Conflict

Conflict

Conflict in Malawi is characteristically tenuous, and there isn’t much connection between conflict in the country and internal Conflict in Malawi is characteristically tenuous, and there isn't much connection between conflict in the country and internal displacement. Where displacement and conflict intersect in Malawi is when civil unrest, typically concerned with politics, rises to the point of violence. The most recent of such occurrences was in 2019 when rioting ensued as a result of the re-election of then-president, Peter Mutharika (Jomo, 2019. There were several claims that the election had been fraudulent and unfair, causing widespread protests (VOA, 2020). The government’s forceful response escalated into human rights violations and forced people from their homes (Pensulo, 2020).

Disaster

Disaster

Natural disasters are common in Malawi because of the climate. This means that flooding, storms, and landslides are major contributors to internal displacement in the country, for example, the Red Cross indicated that 106,879 people were displaced by Cyclone Gombe in the south of Malawi in the Machinga and Manochi districts in February 2022 (Floodlist, 2022).

Immigration

Immigration

Ranked as one of the poorest countries in the world, with 40% of its national budget funded by foreign donors (Khomba & Trew, 2022), Malawi has not been an attractive destination for international migrants. However, it continues to play an essential role as a transit destination for most international migrants. In 2010, the international migrant stock was estimated to be 217,700 (1.5% of the Malawian population) (UN DESA, 2021). In 2015, it was 197,300 (1.2% of the Malawian population) and in 2015, it was estimated to be 191,400 (1.3% of the Malawian population) (Ibid).

It reflects a steady decline in the international migration stock in Malawi. Although there has been a decline in the international migrant stock of women in Malawi from 2010 (113,900) to 2020 (97,800), women constituted more than half of the international migration stock in Malawi (Ibid). This reflects the increased feminization of migration in Malawi. Immigrants in Malawi are primarily from Mozambique, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Burundi, Rwanda, India, Tanzania, Britain, Congo, and South Africa Tanzania (IOM, 2014).

Female Migration

Female Migration

There is no specific information on the nature of the female immigrant population in Malawi. However, the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA) gives general statistics on the total female immigrant population in Malawi without any specificities. Unlike in other parts of Africa where the female immigrant population stock is less than half of the total immigrant population stock (for example, Ivory Coast and South Africa), in Malawi, like in Cameroon and the Democratic Republic of Congo, the female immigrant population stock is more than half of the total immigrant population stock.

Female immigrant population as a percentage of the total immigrant population in Malawi has been stable from 2000 – 2019, hovering between 52.1% to 52.4% (UN DESA, 2019). This reflects an increase in the feminization of the female immigrant population in Malawi.

Children

Children

Malawi is considered a safe transit route for migrants and their children heading for South Africa because of porous borders and relatively relaxed border control. According to UNICEF (2017), South Africa is seen as the economic powerhouse of the continent and thus a magnet for migrant children. Data on the number of migrant children in Malawi do not exist. However, migrant children in Malawi often accompany their parents whose migration status determines the children’s status. Despite legal provisions like the Childcare and Protection Act of 2010 being put in place to prohibit the detention of children, children often experience detention in Malawi for periods between 3 – 8 months because of the irregular status of their parents (Gadisa et al., 2020).

Refugees and Asylum seekers

Refugees and Asylum seekers

As of November 2023, there were 52,760 refugees and asylum seekers in Malawi (UNHCR, 2023). Of these refugees, 34,462 come from other countries, 34,159 from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), 11,576 from Burundi, 6,687 from Rwanda, and 35 from Mozambique (Ibid).

Malawi has an encampment policy, and all refugees and asylum seekers are hosted in the only existing camp, the Dzaleka refugee camp. The camp, initially designed for 10,000 people, now hosts more than 48,000 people, posing serious health risks. Malawi is a transit route for migrants intending to reach South Africa. Some challenges confronting refugees in the Dzaleka refugee camp include a lack of freedom of movement, poor sanitation, and congestion. Although refugees face some of these challenges mentioned above, the government does provide voting rights to refugees after 6 years of residence (SIHMA, 2021).

Although Malawi has an encampment policy, before March 2023, when the government reiterated its position of placing all refugees and asylum seekers in the camp, refugees enjoyed freedom of movement and some of them had established businesses outside of the camp. The March 2023 directives from the government saw the forcible removal of 2,296 refugees and asylum seekers between May and early October 2023, into the Dzaleka refugee camp (Global Detention Project, 2023).

Emigration

Emigration

Historically, Malawi has played the role of labour supplier in the South African mines. Following a period of decline in migration to work in mines in the 1980s, Malawians continued to emigrate to South Africa to seek various jobs in the growing informal sector and for trade purposes (Banda, 2017). According to Reuters (2020), there were about 87,000 Malawians in South Africa constituting 4% of the immigrant population. The total number of emigrants from Malawi in mid-year 2020 stood at 311,100 (UN DESA, 2021). In 1990, half of all Malawian emigrants lived in Zimbabwe, followed by Zambia (14%) and South Africa (11%) (The African Capacity Building Foundation, 2018). However, with the adverse changing economic situation in Zimbabwe and the cessation of hostilities in Mozambique, the share of Malawian migrants in Mozambique rose from 2% to 25% (77,488) by 2015 (Ibid). By 2015, the share of Malawians living in other African countries was as follows; Zimbabwe 102,849, South Africa 76,605, Zambia 11,258, Tanzania 6,907, and Botswana 4,596. Out of Africa, Europe is host to about 19,557 Malawians, the UK hosting a giant portion of 17,871 while Canada and Australia host about 981 and 1,266 Malawians respectively (Ibid).

Also, high population growth, high unemployment, and comparatively low salaries for professionals within the region make the emigration of skilled professionals, particularly attractive to young professionals in Malawi. In Malawi, the country loses more nurses than it trains, causing a strain on the health system and diminishing prospects of achieving the health-related Sustainable Development Goals (The African Building Capacity Foundation, 2018). Estimates indicate that more than half of the nurses trained in Malawi emigrate to the United Kingdom (Ibid). The country at one point, had vacancies in all nursing and clinical cadres with a 75% vacancy rate for nurses, and only 48% of targeted clinical officers and 40% of targeted nurse-midwife cadre were filled (Ibid). Until 1991, Malawian doctors who emigrated were almost entirely those who stayed after training in OECD countries as there were no training facilities in Malawi. However, with the creation of Malawian medical training schools, things have not changed. In 2002, 59% of the 493 doctors born or trained in Malawi were working abroad, causing a massive shortage of medical doctors, particularly in rural hospitals (Ibid).

Nurses are not the only trained professionals who emigrate, trained Malawian teachers also emigrate for better opportunities. Drawing from the administrative records from the Chancellor College University of Malawi, in 20 years, as of 2019, 67 members of academic staff would have emigrated (Ibid). Despite the absence of reliable data on all skilled Malawians living abroad, the Afro Barometer projects that of the 45% of Malawians who consider emigrating, half of them with post-secondary education consider emigrating to Europe and/or North America (Afro Barometer, 2019).

Labour Migration

Labour Migration

Malawi is a signatory to the ILO Migration for Employment (Revised) Convention No. 97 of 1949 and has a national migration and citizenships policy that governs labour migration in and out of the country. This policy seeks to ensure, inter alia, that the country upholds its commitments to national, regional, and international instruments governing labour migration (Malema, 2022). Within the migration policy framework, foreign migrant workers are entitled to the same legal protection, wages, and working conditions as Malawian citizens if they comply with immigration laws. However, immigrants from neighbouring countries, who transit through Malawi, often do so without any legal documents.

They are thus operating in the informal labour market without any legal protection. Nevertheless, the government has launched policies to address the status of those in the informal economy, for example, the National Labour and Employment Policy (NLEP) and the Malawi Decent Work Country Programme (MDWCP). It is also important to note that Malawi is not a signatory to the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and their Families. According to IOM (2014), data from the Immigration Department for 2011 to 2014 indicates that temporary employment permits issued rose from 2,428 in 2011 to 2,842 in 2013, business permits issued over the same period rose from 121 to 175 while temporary employment permits issued from April 2013 to November 2014 stood at 1549.

Human Trafficking

Human Trafficking

Human trafficking is an area of concern in Malawi. Endemic poverty has made Malawians vulnerable to human trafficking. Malawi is a Tier 2 country as the government is making significant efforts in some respects but does not fully meet the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking (US Department of State, 2023). Malawi is considered a source, transit, and destination for victims of human trafficking.

The government of Malawi in 2022, investigated 81 trafficking cases with 46 suspects, prosecuted 46 alleged traffickers and secured the conviction of 24 traffickers (Ibid). Some of the victims of human trafficking in Malawi are identified in the refugee camps (places that are meant to provide protection and assistance to refugees) where they are sold for forced labour and prostitution (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2022). According to the US Department of State (2023), trained camp officials identified 137 victims of human trafficking between 2021 and 2022. In 2021 the government investigated 19 suspected cases of human trafficking and obtained convictions for 17 traffickers in the Dzaleka refugee camp (US Department of State, 2023). The majority of the alleged traffickers were Malawian citizens while others were nationals from Zambia, Mozambique, Pakistan, and China (Ibid).

In Malawi, within the family structure, traffickers exploit family members from the southern part of the country to the central and northern regions for forced labour in agriculture, goat and cattle herding, begging, fishing, brickmaking, and recently others are coerced into stealing (Ibid). Exploitation external to the family involves fraudulent recruitment and physical or sexual abuse. Traffickers typically lure children in rural areas by offering employment opportunities, clothing, or lodging, for which they are sometimes charged exorbitant fees resulting in labour and sex trafficking coerced through debts (Ibid). Sadly, Malawian victims of trafficking have been identified in South Africa, Kenya, Mozambique, Tanzania, Zambia, Iraq, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia (US Department of State, 2023).

To mitigate the suffering of victims of human trafficking in Malawi, the government launched standard operating procedure (SOP) and national referral mechanisms (NRM) through which it referred all victims to Non-Governmental Organisations where they receive counselling, medical care, shelter, food, and livelihood training. However, these services are inadequate, for example, because of inadequate shelter victims are put in detention centres where some of them run away because of lack of food (US Department of State, 2021). Several challenges hamper the government’s ability in the fight against human trafficking in Malawi which include inadequate staff, inadequate resources, and a conflation of the concept of human trafficking and human smuggling (US Department of State, 2023).

Remittances

Remittances

With the high levels of poverty and unemployment in Malawi, remittances play a very important role in reducing household poverty. According to Truen et al. (2016), remittances have a positive impact on agricultural productivity, household income, and child education and reduce school dropouts in Malawi.

According to Dhakal (2022), remittances contribute to food security, particularly in urban cities where access to food largely depends on the availability of cash. According to the World Bank (2022), Malawi experienced a steady increase in remittance flow from 2011 ($25,320,231) to 2015 ($41,493,977). It experienced a slight decline in 2016 ($39,053,133) and picked up in 2017 ($78,392,830) to its all-time high in 2019 ($268,194,658). With the outbreak of Covid-19 personal remittances fell by 0.4 percentage points from 2019 to 2020, where it stood at $215,397,931. According to Reuters (2020), remittances paid through the official channels fell by 30% during the first eight months of 2020. Remittances as a percentage of the Gross Domestic Product constituted 0.3% in 2011 to 2.4% in 2019 (World Bank, 2022). Because of its direct impact on households, any fluctuation in the flow of remittances will have a measurable impact on the household.

Returns and Returnees

Returns and Returnees

As a result of the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic and the subsequent lockdown regulations that ensued, many migrant workers, especially in the informal economy, were jobless. The effect of the pandemic was an increase in returnees to Malawi. According to VOA (2021), the Malawian immigration department reported receiving more than 10,000 Malawian returnees from South Africa since the outbreak of the pandemic. Also, IOM assisted 397 stranded Malawian migrants to return from Zimbabwe (IOM, 2021). All returnees were expected to quarantine in a government facility. Returnees complained of poor living conditions in such facilities. They were scapegoated as carriers of disease, and some returnees feared rejection by family members because they were poor.

International Organisations

International Organisations

The key international organisations dealing with migration-related issues include the IOM (International Organisation for Migration) and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Since 2014, the IOM has been very active in Malawi. It has contributed enormously to the government’s effort to manage migration through a wide variety of projects and programmes which include amongst others assisting the government in developing the first-ever migration profile, assisting in the voluntary return and reintegration of Malawians, refugee resettlement, migration, health, and combating trafficking in persons and human smuggling. The UNHCR supports the government in its lead in the refugee response plan. Some of the UNHCR's main activities which assist refugees in Malawi are in the areas of education, health, community empowerment, and self-reliance. Other migration-related United Nations agencies in Malawi include Plan International which advances children’s rights and equality for girls including refugees, the World Food Programme (WFP) which works to achieve and maintain food security among refugees, transitioning from monthly food distribution to cash-based transfers, and the Moravian Church that has a presence in the Dzaleka refugee camp, providing, for example, food relief parcels to refugees in the camp.

Afro Barometer. 2019. Almost half of Malawians consider emigration; most-educated are most likely to look overseas. Retrieved from: https://www.africaportal.org/documents/18907/ab_r7_dispatchno281_malawi_emigration.pdf.

Anglewicz, P., Kidman, R., & Madhavan, S. 2019. Internal migration and child health in Malawi. Social Science & Medicine. Retrieved from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0277953619303740.

Banda, C. 2017. Migration from Malawi to South Africa: A historical and cultural novel. Langaa RPCIG, Cameroon.

Boeder, B. 1984. Malawian labour migration and international relations in Southern Africa. Africa Insight, Vol. 14(1):17-25

Chilanga, E., et al. 2017. Food security in informal settlements in Lilongwe. Southern African Migration Programme. Retrieved from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvh8qz6k.

Chilunga, F., Musicha, C., Tafatatha, T., Geis, S., Nyirenda, J., Crampin, C., & Price, J. 2019. Investigating associations between rural-to-urban migration and cardiometabolic disease in Malawi: a population – level study. International Journal of Epidemiology, Vol. 48(6):1850-1862. Retrieved from: https://academic.oup.com/ije/article/48/6/1850/5585827.

Chirwa, C. 1994. Alomwe and Mozambican immigrant labour in colonial Malawi, 1890s – 1945. The International Journal of African Historical Studies, Vol. 27(3):525-550

CIA World Factbook. 2023. Malawi. Retrieved from: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/malawi/.

Dinkelman, T. & Mariotti, M. 2016. The long run effect of labour migration on human capital formation in communities of origin. NBER Working Paper Series. Retrieved from: https://www.nber.org/papers/w22049.

Floodlist. 2022. Mozambique – Death toll from Cyclone Gombe rises to more than 50. Retrieved from: https://floodlist.com/africa/mozambique-cyclone-gombe-update-march-2022.

Gadisa, G., Sibanda, O., Vries, K., & Rono, C. 2020. Migration-related detention of children in Southern Africa: Development in Angola, Malawi and South Africa. Global Campus Human Rights Journal, Vol. 4:403-423.

Global Detention Project. 2023. Malawi’s encampment policy: Forced relocation and detentions. Retrieved from: https://reliefweb.int/report/malawi/malawis-encampment-policy-forced-relocations-and-detentions.

Government of Malawi. 2019. 2018 Malawi population and housing census. Retrieved from: https://malawi.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/2018%20Malawi%20Population%20and%20Housing%20Census%20Main%20Report%20%281%29.pdf.

IDMC. 2022. Malawi. Retrieved from: https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/malawi.

IOM. 2014. Migration in Malawi: A country profile. Retrieved from: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/mp_malawi.pdf.

IOM. 2021. IOM facilitates return home for growing trend of irregular migration between Malawi and Zimbabwe. Retrieved from: https://www.iom.int/news/iom-facilitates-return-home-growing-trend-irregular-migration-between-malawi-and-zimbabwe.

Jomo, K. 2019. Protesters loot in Malawi as president challenge goes to court. Bloomberg. Retrieved from: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-08-06/election-dispute-in-malawi-heats-up-as-fresh-protests-erupt.

Khomba, C. & Trew, A. 2022. Aid and local growth in Malawi. Retrieved from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00220388.2022.2032668.

Malawi: Refugee Act of 1989, 8 May 1989. Retrieved from: https://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b4f28.html.

Malema, K. 2022. Labour migration governance: Analysis of the failed Malawi labour migration programme – lessons learnt. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/360837320_Labour_Migration_Governance_Analysis_of_the_Failed_Malawi_Labour_Migration_Programme_-_Lessons_Learnt.

Migration Data Portal. 2020. International migration stock – Malawi. Retrieved from: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/.

Pensulo, C. 2020. “It’s the year of Mass protests”. Malawi awaits crucial election ruling. Retrieved from: https://africanarguments.org/2020/01/year-mass-malawi-protests-election-ruling/.

Reuters. 2020. Dreams dashed: Malawi migrants return empty-handed from South Africa. Retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-malawi-migrants-health-coronavirus-idUSKBN2741GN.

SIHMA. 2021. Refugees in Malawi, Migrants’ Right to Vote. Retrieved from: https://sihma.org.za/Blog-on-the-move/refugees-in-malawi-migrants-right-to-vote-and-mandela-day-globally.

The African Building Capacity Foundation. 2018. Brain drain in Africa: The case of Tackling Capacity Issues in Malawi’s Medical Migration. Retrieved from: https://elibrary.acbfpact.org/cgi-bin/acbf?a=d&d=HASH37e230bc5b6e0d2a16d383&gg=0.

The African Capacity Building Foundation. 2018. Brain drain in Africa: The case of tackling capacity issues in Malawi’s medical migration. Retrieved from: https://www.africaportal.org/publications/brain-drain-africa-case-tackling-capacity-issues-malawis-medical-migration/.

Truen et al. 2016. The impact of remittances in Lesotho, Malawi and Zimbabwe. Finmark Trust. Retrieved from: https://finmark.org.za/system/documents/files/000/000/247/original/the-impact-of-remittances-in-lesotho-malawi-and-zimbabwe.pdf?1602597191.

UN DESA. 2021. Profile: Malawi. Retrieved from: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/.

UN DESA. 2019. International migration stock 2019: South Africa. Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates2/estimates19.asp.

UNDP. 2022. Malawi National Human Development Report 2021. Retrieved from: https://hdr.undp.org/content/malawi-national-human-development-report-2021.

UNHCR. 2023. Malawi. https://data.unhcr.org/en/country/mwi.

UNHCR. 2021. Malawi – Data Portal. Retrieved from: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjno6Ck_O7xAhUWHcAKHTvZDeYQFjAAegQIBxAD&url=https%3A%2F%2Fdata2.unhcr.org%2Fen%2Fcountry%2Fmwi&usg=AOvVaw36nqFoBXhfW7Z6KMWk5Uvc

UNICEF. 2017. Children on the move: Unaccompanied migrant children in South Africa. Retrieved from: http://www.childlinesa.org.za/wp-content/uploads/children-on-the-move-unaccompanied-migrant-children-in-south-africa.pdf.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2021. UNODC & Malawi launch new measures to combat human trafficking among refugees. Retrieved from: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/frontpage/2021/April/unodc-and-malawi-launch-new-measures-to-combat-human-trafficking-among-refugees.html.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2022. Refugees at risk: UNODC uncovers human trafficking at camp in Malawi. Retrieved from: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/human-trafficking/Webstories2022/refugees-at-risk_-unodc-uncovers-human-trafficking-at-camp-in-malawi.html.

US Department of State. 2021. Trafficking in Person report: Malawi. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2021-trafficking-in-persons-report/malawi/.

US Department of State. Trafficking in person report: Malawi. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-trafficking-in-persons-report/malawi/#:~:text=In%202021%2C%20the%20government%20investigated,of%2014%20years%20of%20imprisonment.

VOA. 2020. Malawi anti-bribery protests draw thousands. Retrieved from: https://www.voanews.com/a/africa_malawi-anti-bribery-protests-draw-thousands/6182719.html.

VOA. 2021. Malawi mandates quarantine for returnees from South Africa. https://www.voanews.com/a/covid-19-pandemic_malawi-mandates-quarantine-returnees-south-africa/6200409.html.

World Bank. 2022. Personal Remittance received, (% of GDP): Malawi. Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.TRF.PWKR.DT.GD.ZS?locations=MW.