A Comparison Between South African and United States’ Immigration Policy

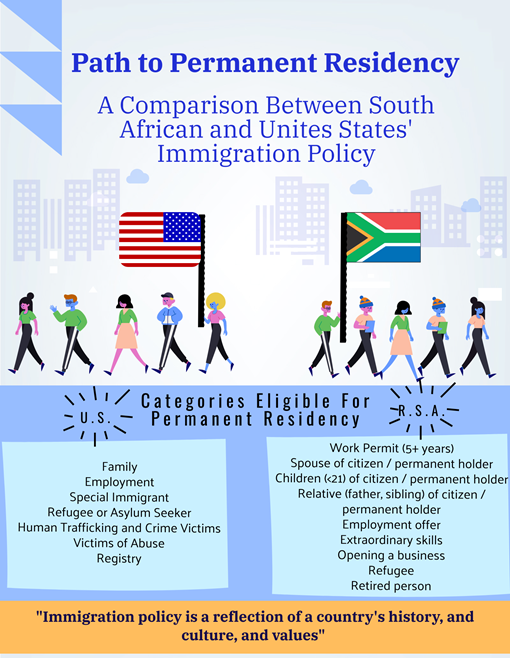

Comparison and Path to Permanent Residency:

Acquiring permanent residence in a country other than your birth country comes with trials and tribulations. As of 2019, the number of international migrants stood at approximately 272 million, making up 3.5 percent of the world’s population (1). In South Africa, the number of international migrants stands at approximately 4.2 million, and South Africa is the country with the largest number of international migrants on the African continent with the second largest being Côte d’Ivoire (2.5 million) (2). In the United States, that number is almost 51 million which dwarfs the world’s next largest countries international migrant stock figure being Germany and Saudi Arabia which each have 13.1 million international migrants (3). The reason for the prominence of international migrants in South African from the African continent perspective and in the US from the global perspective may be as a result of the relative size and stability of the countries’ economies as well as the proximity to countries from which people readily migrant among other reasons. Migration to wealthier and more developed countries results in ‘loss of trained and educated individuals to emigration. For example, there are currently more African scientists and engineers working in the U.S. than there are in all of Africa, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM) (4).

Generally speaking international migration has a net positive impact on the receiving country’s economy contributing significantly to the workforce in the labour market, to the public purse and to economic growth (5). Thus it may also be argued that the success of the United States economy and of the South African economy is owed in part to their sizable international migrant populations that they host. However, how is this reflected in each country’s policies and in the political rhetoric with respect to migration? Regrettably, in recent history the political rhetoric in the US (6) and in South Africa (7) and the accompanying policy and legislative development (8), with respect to international migration has been the converse of what is expected given the positive economic impact of receiving international migrant. Politicians and policy have been anti-migrant and xenophobic with migrants being readily criticized, referred to by dehumanising terms like ‘illegals’ or ‘criminals’ and are often used by politicians as scapegoats for poor service delivery (9). keeping migrants out of the country and deporting those who have entered is increasing becoming the order of the day. For example the ‘build a wall’ political slogan from the US Republican Party and the redirecting of 1.5 Billion USD on replacing sections of the border fence with a wall (10) and implementation of travel bans, not to mention the labelling of certain African countries with expletives, is not far different from the South African government spending 37 Million Rand on border fencing (11), increasing the categories of undesirable persons and banned international migrants and speaking with distain about migrants from certain countries (7).

One of the fundamental goals for most migrants in integration. Integration of international migrants manifests ultimately in permanent residence and then citizenship. The process to acquire permanent residence not only requires personal determination and grit, but also involves sometimes complex (and potentially unfair) migration policies and legal barriers.

Current South African migration legislation is rooted and embodied in the Immigration Act of 2002 which is to be read along with certain other statutes (eg Refugees Act 130 of 1998 and Citizenship Act 88 of 1995 and Births and Deaths Registration Act 51 of 1992). The purpose of the Immigration Act is “to provide for the regulation of admission of persons to, their residence in, and their departure from the Republic; and for matters connected therewith” (12). In simple terms, the Immigration Act particularly through sections 25 to 27 (12) establishes the pathway to permanent residency, among other immigration matters. The Act outlines the particular requirements which are to be met by an applicant who wishes to move permanently to South Africa. The South African High Commission states that the requirements are:

● The applicant must be of good character

● He/she must be a desirable inhabitant

● He/she must not be likely to be harmful to the welfare of the Republic of South Africa

● [and in the case of in terms of residency flowing from exceptional skills or a work permit]… he/she must not follow an occupation in which there is already a sufficient number of persons available to meet the requirements of the country (13)

The last requirement is not relevant for someone obtaining permanent residence through a number of categories such as through spousal relationship, kinship, or refugee status. The three and in certain cases 4 requirements aim to make the process slightly more selective in order to protect the inherent rights of South African citizens and to bolster the economy (13). The Immigrants Selection Board, an independent, autonomous statutory body, considers all applicants first on the three to four grounds above. Once those basic requirements have been met, those eligible to apply must fall into one of various categories. The Immigration Act of 2002 outlines the categories as such:

● A person who has been the holder of a Work Permit for 5 years;

● The spouse of a South African Citizen or Permanent [Residence] Holder;

● The child under the age of 21 years or a South African citizens or Permanent Residence

holder;

● A person who received an offer of employment;

● A person who has extraordinary skills;

● A person who is opening a business;

● A refugee[, meeting the requirements of Section 27(c) of the Refugees Act];

● A retired person;

● A relative of a South African citizen or permanent resident holder (restricted to mother,

father, or brother and sisters) (13)

South African immigration policy is designed to select the individuals who will either add to the economy and “invest their assets, skills, knowledge, and experience for the benefit of themselves and the people of South Africa” (13), or individuals who are seeking family unity and/or safety. The process to obtain permanent residency in South Africa is grounded in the basic principles of providing individuals with greater flexibility, greater security, and a state of permanency and stability. Permanent residency is closely guarded, and certain categories are intensely scrutinised such as spousal visa leading to permanent residence and certain migrants were denied the right to marry altogether until the court intervened (14). Other categories take incredibly long periods to obtain, such as refugee status to obtain permanent residence. For refugees after spending years to over a decade in the asylum determination process and then getting formal recognition of refugee status, as of the beginning of 2020, they have to have refugee status for more than 10 years (previously only 5 years) before they may be considered for permanent residence in terms of recent amendments to the Refugees Act 130 of 1998 (15) which came into force in January 2020. Thus someone fleeing persecution or war and seeking asylum may spend in excess of 20 years in South Africa before they become eligible to be considered and then would still have to prove that they will be a refugee indefinitely in term of the Refugees Act before being granted certification to apply for permanent residence in terms of the Immigration Act.

The United States, having a far greater influx of immigrants every year, has a more complex and strict immigration system. Immigration law is so nuanced that the average U.S. citizen is unlikely to be able to describe even the basic qualifications and processes. The current body of law that governs immigration policy is called the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), enacted in 1952. The INA “collected many provisions and reorganized the structure of immigration law. The INA has been amended many times over the years and contains many of the most important provisions of immigration law” (16). Every year, the INA allows the United States to grant up to a total of 675,000 permanent immigrants visas across various categories (17). This excludes visas granted to the spouses, parents, and children of current U.S. citizens (17). In addition to these 675,000 visas allowed, each year the President of the United States and Congress agree upon an annual number of refugees to be admitted through the U.S. Refugee Resettlement Process (17). In September 2019, the Trump administration reduced the resettlement cap by almost half and this was the third cut with Refugee resettlement figures reduced by 80% from what they were in the last year of the Obama Administration (18). This reduction in refugee protection and provision by the US may be liken to the reduction on refugee protection and provision in South Africa including through recent legislative amendments (15). In terms of permanent residence, similar to South African immigration policy, the INA has established seven main categories in which an applicant must fall into (17):

● Family

● Employment

● Special Immigrant (religious worker, international broadcaster, etc.)

● Refugee or Asylee Seeker

● Human Trafficking and Crime Victims

● Victims of Abuse

● Registry (have resided continuously in the U.S. since before Jan. 1, 1972)

These seven categories establish the basis of immigration policy. Furthermore, applicants may also be eligible under a miscellaneous category which details more obscure reasons for immigration based on previous acts of legislation. For example, under this miscellaneous category is the Cuban Adjustment Act, which grants Cuban natives and their spouses and/or children permanent residence eligibility. (16) Other subcategories include First Nation / Native Americas born in Canada, and those individuals born in the United States to foreign diplomatic officers. In this sense, the Immigration and Nationality Act is largely built from political history. Furthermore, within each of the main seven categories, there are detailed subcategories that an applicant must fall into, once again proving the complexity of United States immigration policy.

One last important distinction to be drawn between South African and United States immigration law is the stress, and lack thereof, on placing a limit on the number of migrants from each country. While the Republic of South Africa does not establish limits, the INA places a limit on how many immigrants can come to the U.S. from any one country. No one group of permanent immigrants (family based and employment based) from a single country can exceed seven percent of the total number of people immigrating to the United States in a single fiscal year (17). This provision of the law is intended to prevent any immigrant group from dominating immigration patterns to the United States (17).

The immigration policies of each country have been formed through years of political conflict and strife, fluctuations in the economy, and changing administrations and leadership. Immigration policy is a reflection of a country’s history, and culture, and values. There is so much to uncover and learn about the immigration policies and practices of different nations. This publication seeks to provide a simplified overview of the policies in South Africa and the United States, but it only scratches the surface of what is to be learnt.

James Chapman and Nell Fredericks

SIHMA SIHMA

Project Manager Research and Communication Intern

References:

- https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/international-migrant-stock-2019.html

- https://migrationdataportal.org/data?i=stock_abs_&t=2019&m=1&rm49=2&cm49=800

- https://migrationdataportal.org/?i=stock_abs_&t=2019

- https://www.globalization101.org/economic-effects-of-migration/

- https://www.oecd.org/migration/OECD%20Migration%20Policy%20Debates%20Numero%202.pdf

- https://www.newsday.com/opinion/commentary/donald-trump-coronavirus-xenophobia-china-covid-19-racism-1.43314898 and also see: https://www.nytimes.com/video/us/politics/100000007372113/trump-biden-ilhan-omar-minnesota.html

- https://mg.co.za/article/2019-09-03-00-xenophobia-and-party-politics-in-south-africa/

- https://businesstech.co.za/news/business/364176/tough-new-laws-for-refugees-in-south-africa/

- https://allafrica.com/stories/202009230734.html

- https://www.cbsnews.com/news/pentagon-shifting-1-5-billion-for-border-wall-construction-defense-department-announced-today-2019-05-10/

- https://www.sabcnews.com/sabcnews/r37-million-beit-bridge-border-fence-not-fit-for-purpose-scopa-chair/

- http://www.saflii.org/za/legis/num_act/ia2002138.pdf

- https://www.sahc.org.au/immigration.htm

- https://www.iol.co.za/news/politics/home-affairs-ban-on-asylum-seekers-getting-married-is-unconstitutional-sca-rules-35513246#:~:text=File%20picture%3A%20Pixabay-,Home%20Affairs'%20ban%20on%20asylum%20seekers,married%20is%20unconstitutional%2C%20SCA%20rules&text=If%20you%20are%20an%20asylum,to%20enter%20into%20a%20marriage.

- http://www.saflii.org/za/legis/num_act/raa201711o2017g41343231.pdf

- https://www.uscis.gov/laws-and-policy/legislation/immigration-and-nationality-act

- https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/how-united-states-immigration-system-works

- https://www.npr.org/2019/09/26/764839236/trump-administration-drastically-cuts-number-of-refugees-allowed-to-enter-the-u

Categories:

Tags: