Covid-19, tourism and migration in Africa

Covid-19 has forced countries all over the world to impose travel restrictions and social distancing measures, leading to the shutdown of hospitality and tourism operations with the consequences of drastically reducing migration and tourism worldwide. The South African Department of Tourism annually runs a Tourism Month campaign in the month of September, culminating with the United Nations World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO) World Tourism Day on September 27th, making it a good time for SIHMA to address the impact of Covid-19 on tourism and migration in Africa. In 2020 the theme of UNWTO World Tourism Day is ‘Tourism and Rural Development’(1) while last year’s theme was ‘Tourism and Jobs, a better life for all.’(1)

While tourism is currently at the center of attention in Covid-19 relief efforts, the consequences of Covid-19 on migrants working in tourism are often overlooked. Yet, migrants are one of the most vulnerable groups to the virus and one of the most affected by current unemployment in the tourist industry. Many people working in tourism are irregular migrants working in the informal sector and in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) who cannot rely on a capital to survive the current crisis. Women are also particularly affected as they represent 54% of the workers in tourism worldwide with a majority in low-skilled or informal work(2).

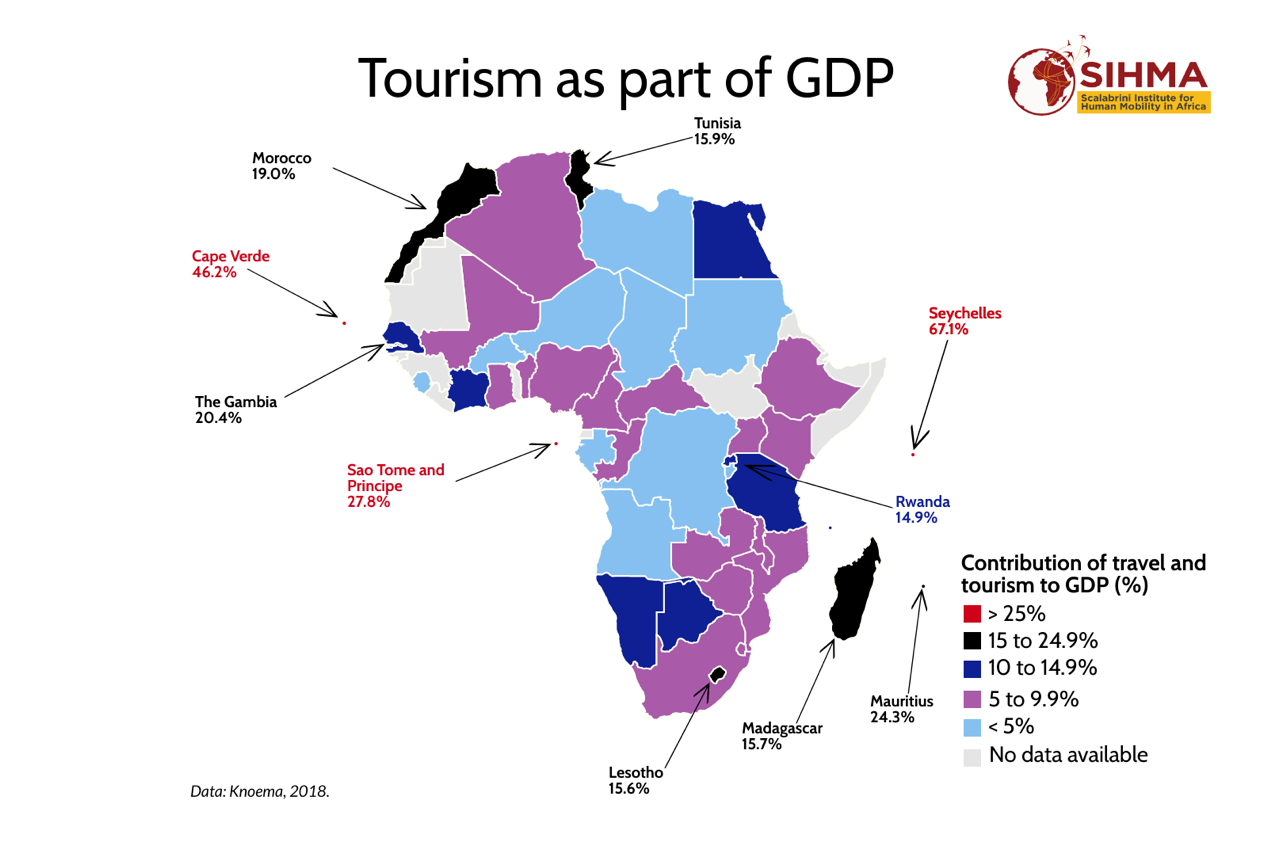

Although African countries are not in the world’s top 30 tourism destinations and only five African countries are in the top 60 tourism destinations(3), tourism is a booming industry on the continent and some economies dependsignificantly on tourism.The top 10 African countries receiving the most international tourism arrivals in 2018 were Morocco, Egypt, South Africa, Tunisia, Nigeria, Mozambique, Algeria, Zimbabwe, Côte d'Ivoire and Botswana(3).Other African countries are also impacted by the reduction of tourism, especially those where tourism contributes to a large part of their GDP(4).

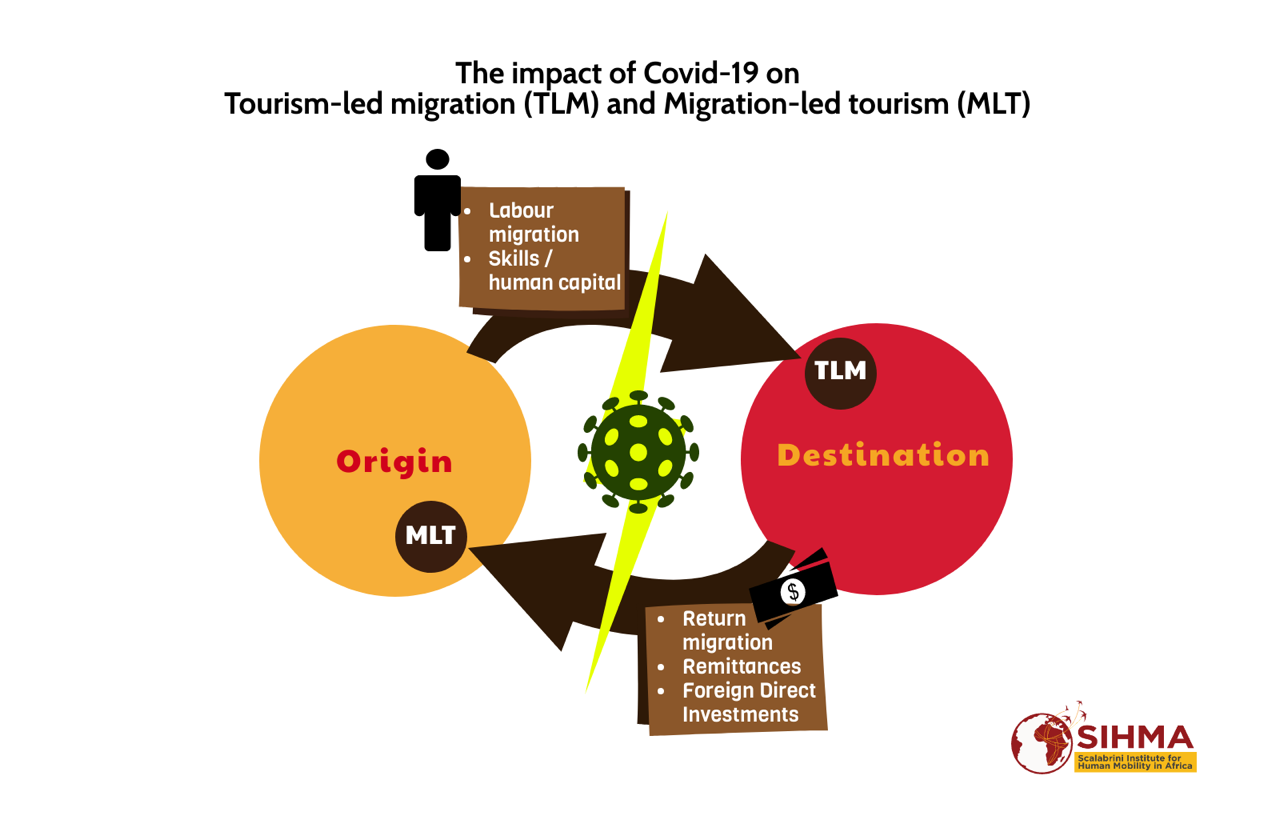

To understand how different economies and migrant labour force are connected in the tourism industry, we must distinguish between tourism-led migration (TLM) and migration-led tourism (MLT).

Tourism-lead migration is when migrants leave their origin country in order to work in the tourism industry in the destination country. According to the UNWTO, tourism is increasingly dependent on migrant labour in destination countries(5). Migrants are working in the formal tourism sector (FTS) – in hotels, restaurants, lodges, airports, on cruise ships etc. – as well as in the informal tourism sector (ITS) – souvenir trade and diverse services (including prostitution).For instance, in Zanzibar, migrants from mainland Tanzania and Kenya represent ¾ of the ITS workers(6). These jobs are relatively easy to access as they don’t necessitate high skills and qualifications and are in high demand in the destination. However, in both the formal and informal sector, migrants are put in vulnerable positions, which are amplified in the current pandemic.

In the ITS, migrants have little to no access to social benefits and Covid-19 stimulus packages(7). This leaves them limited sources of livelihood and deepens their vulnerability. For instance, in South Africa, following lockdown measures, most migrants working in the informal sector – mainly from Zimbabwe, Lesotho, Malawi, Namibia, Eswatini, and Zambia(8)– have lost their jobs and a lot have had to return home(9). Even formal employment does not necessarily provide security for migrants. Migrants working in the FTS, especially those on temporary contracts are facing more difficulties due to Covid-19 than other workers as they can be laid off with little to no protection.

Job losses in the formal and informal tourism sectors in the destination countries also impact migrants’ countries of origin. Indeed, many African countries depend on migration-lead tourism (MLT), i.e. tourism opportunities driven by migration out and back to the country of origin. Return migration, Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) and remittances play a big part in this.

Return migration, whether permanent or temporary, is a driver of economic growth in a number of Africa countries. Expats tourists spend more than domestic tourists when visiting their home country(5). Returnees are also likely to use the skills and experience learned abroad to become entrepreneurs in their countries of origin. In 2019, Ghana was celebrating the ‘Year of Return’ and encouraging Ghanaians abroad to visit and invest in Ghana, in particular in tourism and construction(7).

Migrants are indeed more likely to invest in projects in their countries of origin from abroad than they may otherwise have. Foreign Direct Investments, though decreasing, are still important drivers of development in Africa, connecting migrants to their country’s economy. Tourism is one of the most promising sectors to do so as they acquired the network, cultural knowledge and language skills necessary to attract international tourists. By preventing travel between origin and destination countries, Covid-19 restrictions have a harsh economic impact on countries depending on return migration.

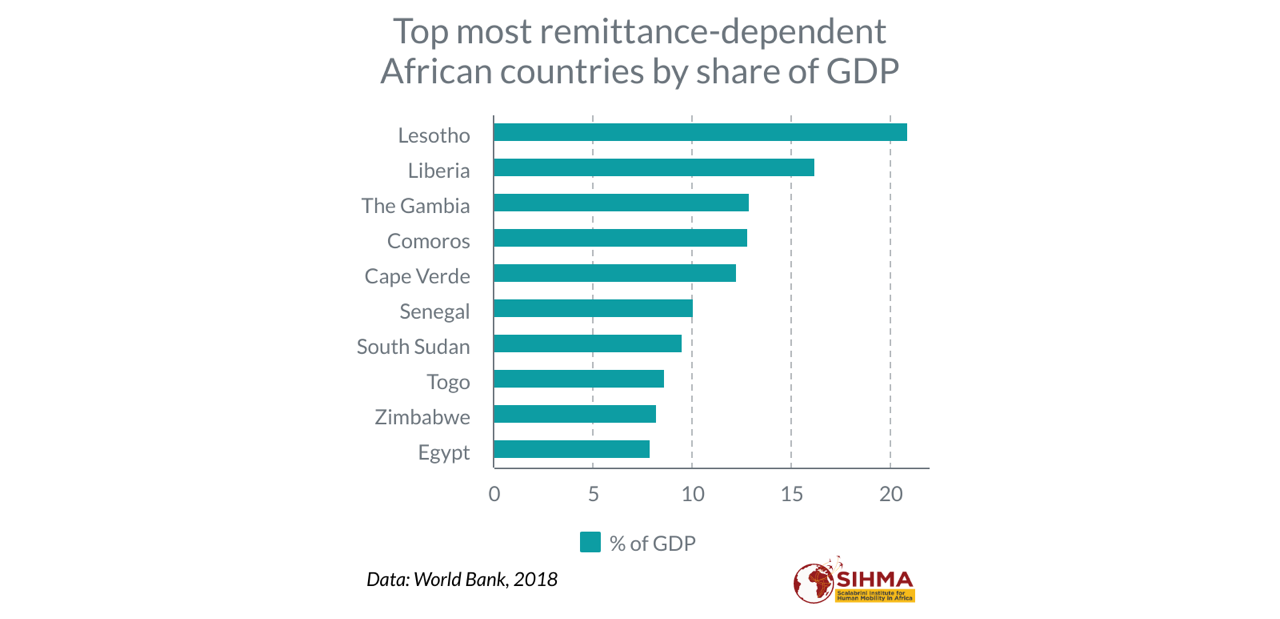

Last but not least, African economies rely on remittances. Remittances are cash and non-cash items flowing through formal channels, such as electronic wiretransfers, or through informal channels, such as money or goods carried across borders, sent by migrants to their respective home countries(5). A lot of African countries depend on remittances for their GDP, such as Lesotho (20.9% of GDP), Liberia (16.2%), The Gambia (12.9%) and Comoros (12.8%)(10).

As the UNWTO points out, remittances constitute a powerful instrument for enhancing tourism-related investments in infrastructure at the community level and for creating small tourism businesses in the country of origin(5). Migrants losing their jobs abroad thus not only affect their social and economic status in the destination country, but also the development of tourism and broader economic growth in their country of origin.

According to the World Bank, Covid-19 has affected remittance flows in an unprecedented manner: in the first half of the year only, 2020 registered the highest historical decline in remittances of about 20% worldwide(11). In Africa, this may push 27 million people into extreme poverty(10).

Migration and tourism are both natural phenomena that are seriouslyaffected by Covid-19 and they are also likely to continue to be affected after the pandemic slows down.

It is crucial to acknowledgeboth the importance of tourism for migrants andthe importance of tourism-led migration for development in countries of origin. Through return migration, FDI and remittances sent by migrants working in tourism, MLT can significantly contribute to development and poverty alleviation(5).

The relationship between migration and tourism is still largely understudied, especially on the African continent. The latest report on tourism and migration by the UNWTO is already 10 years old and there is a lack of reliable data to understand this phenomenon in detail(5).

Covid-19 revealed a number of social issues in tourism existing prior to the crisis. Relief efforts should not only aim at surviving the crisis but they should be seen as an opportunity to reshape the rules of tourism to address social issues and promote secure jobs. The protection of migrant workers’ rights and the protection of female migrants(2) should be at the core of these relief programs, regardless of migratory status(12).

James Chapman and Nolwenn Marconnet

SIHMA SIHMA

Project Manager Research and Communication Intern

Resources:

1. Department of Tourism of South Africa, 2020. https://www.tourism.gov.za/CurrentProjects/Tourism_Month_2020/Pages/Touris_Month_2020.aspx and Department of Tourism of South Africa, 2019. https://www.gov.za/TourismMonth2019

2. UNWTO, 2020. https://www.unwto.org/covid-19-inclusive-response-vulnerable-groups

3. World Bank Data, 2018. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ST.INT.ARVL?locations=ZG-ZQ&most_recent_value_desc=true

4. Knoema, 2018. https://knoema.com/atlas/topics/Tourism/Travel-and-Tourism-Total-Contribution-to-GDP/Contribution-of-travel-and-tourism-to-GDP-percent-of-GDP

5. Tourism and Migration, UNWTO, 2010. https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284413140

6. Stefan Gössling and Ute Schulz, Tourism-related Migration in Zanzibar, Tanzania, 2006. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1461668042000324058?scroll=top&needAccess=true

7. Amanda Bisong, Pamella Eunice Ahairwe and Esther Njoroge, ECDPM paper, 2020. https://ecdpm.org/publications/impact-covid-19-remittances-development-africa/

8. Statistics South Africa, 2016.http://www.statssa.gov.za/?page_id=6283

9. Cohen and Vecchiatto, 2020.https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-25/exodus-by-migrant-workers-undermines-south-africa-virus-lockdown

10. UNECA, 2020. https://www.uneca.org/sites/default/files/PublicationFiles/eca_covid_report_en_rev16april_5web.pdf

11. World Bank, 2020. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/04/22/world-bank-predicts-sharpest-decline-of-remittances-in-recent-history

12. OHCHR, 2020. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=25730&LangID=Ehttps

Photo by Joshua Kraus on Unsplash

Categories:

Tags: