Exclusion of migrant women | Access to health care

Continuing the Series on Migrant Women.

In the first edition of SIHMA’s series on the exclusion of migrant women, we discussed the particular lack of access to the labour market and the exclusion of migrant women from labour-related policy making (1). This second article addresses the even more intimate issue that is physical and mental well-being and access to health services. Indeed reports, such as the 2018 World Health Organization (WHO) reports entitled “Women on the move – Im[m]igration and health in the WHO African region” (2) and “Health of Refugees and Migrants” (3) show, migrant women are facing unique health risks related to the intersection of gender and other social parameters including age, education, income level and legal status.

Regardless of status and reason for migration, African migrant women face enormous challenges throughout the migratory process, whether pre-migration, in transit, on arrival in destination, and in some cases when re-entering and reintegrating into their country of origin (2). Yet, they remain largely invisible.

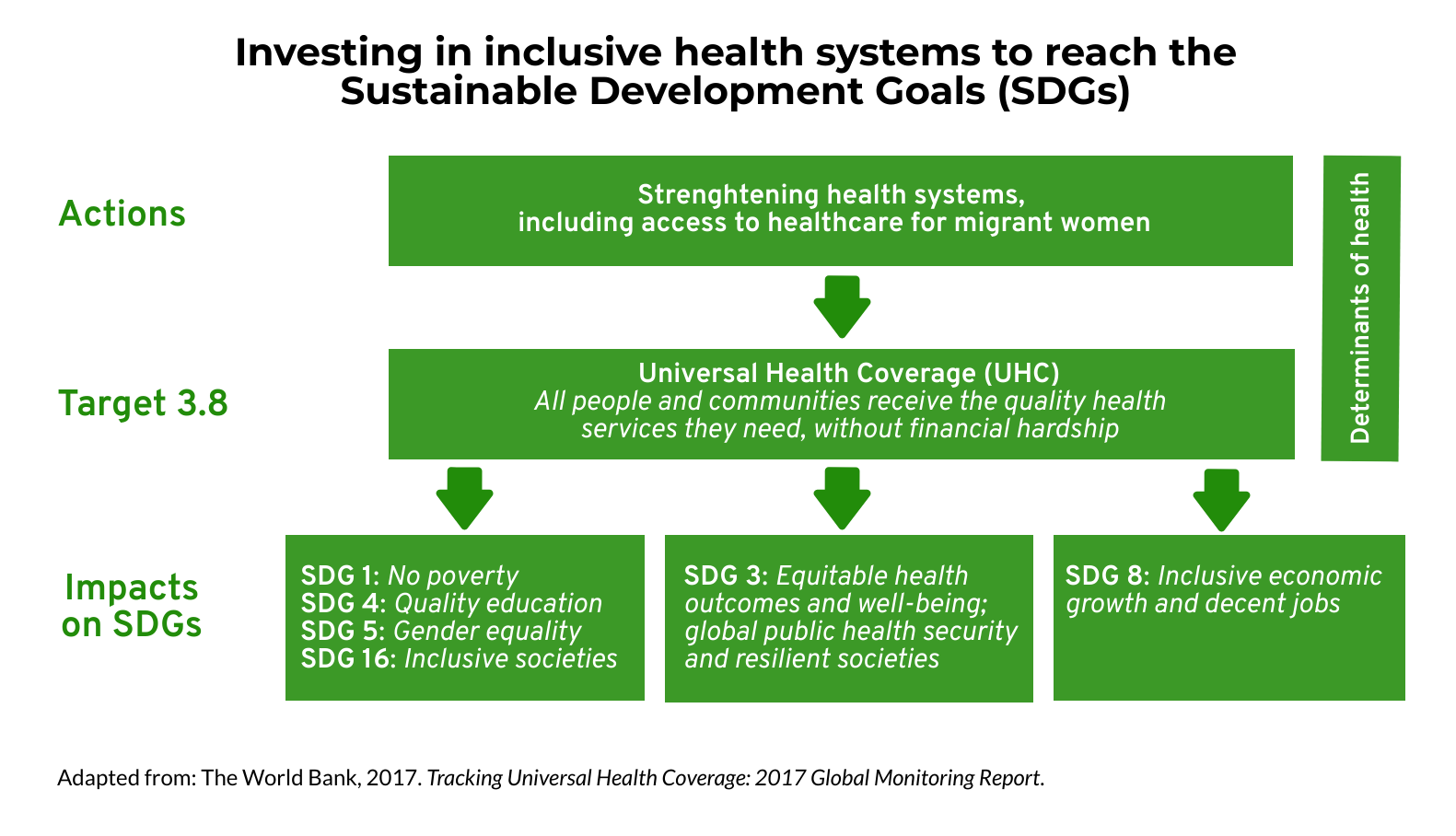

The lack of access to health services for migrant women is not only undermining their personal well-being, but is also preventing the whole continent from achieving the Sustainable Development Goals of gender equality, non-discrimination and universal health coverage (UHC) for all Africans.

Investing in health systems to reach UHC and the SDGs (7)

Migrant women have specific health needs.

Migrant women in Africa are exposed to high health risks at various stages of migration. Migration can have a devastating effect on their physical, mental, emotional, and sexual health.

In destination countries, for instance, refugees, asylum seekers, irregular migrants and trafficked women and girls often end up living in insanitary conditions, such as overcrowded slums, where they are exposed to a high risk of illness, physical and sexual violence, forced labour and sometimes forced to use drugs and alcohol (2).

So called economic migrants work in different sectors depending on their gender. Women are more likely to work in less regulated and less visible jobs such a domestic and care work, and thus are more vulnerable to gender-based violence, exploitation, trafficking, forced sexual labour and sexual assault, leading to harmful reproductive and sexual health consequences. Human Right Watch recorded numerous cases of physical abuse, sexual harassment, and rape, particularly when migrating from various African and Asian countries (including in excess of 30 000 domestic workers from Ethiopia) to the Oman in the Middle East (4). The Human rights watch report also notes that at times migrant domestic workers from Cameroon, Ethiopia, Guinea, Kenya and Senegal were banned from migration ‘on the dubious grounds of preventing “the spread of diseases from these African countries to Oman”...’ In 2020 similar discrimination and xenophobic lead to thousands of Ethiopian workers being deported to Ethiopia from Saudi Arabia and the UAE on unsubstantiated grounds of health risks without testing (20). This labelling Ethipian migrants as a health risk and returning them happened despite infection levels and infection rates being far lower in Ethiopia than in Saudi Arabia. Migrants lost their livelihoods being returned from areas with high levels of infection and infection rates to their country with potential serious health repercussions (20). The UN spoke out against these deportations and the risk further extensive spreading of the virus (21).

As a result the public outcry against deportations the deportations were halted. However, many migrants were instead detained and remain in Saudi Arabia under appalling conditions under which overcrowding (eg between 300 and 500 women and girls in one room (22)), disease and lack of medical care for migrants, including women and girls, is commonplace. Pregnant migrant women and children are at serious risk in detention (23). ‘Detainees say there are a significant number of pregnant women in detention. Roza, 20, who was six months pregnant at the time of interview, said there were 30 other pregnant women in her cell... None of the pregnant women Amnesty talked to or heard about were receiving adequate health care (23).’ Marie Forestier, from Amnesty International said: “Pregnant women, babies and small children are held in these same appalling conditions, and three detainees said they knew of children who had died. We are urging the Saudi authorities to immediately release all arbitrarily detained migrants, and significantly improve detention conditions before more lives are lost.”

Talking about health care for women also often means the health of children, as women are generally their primary care givers. Migrant women meet numerous obstacles to access maternal and child services. Irregular migrants and female sex workers, because their status and activities are perceived as criminals, marginalised and end up being forgotten by health promotion campaigns, leading to high maternal mortality rates and chronic disease outbreaks due to low vaccination coverage for children of migrant women, as the WHO reported in Kenya (5).

Thus, taking care of women migrants also means taking care of children and adolescents’ health, including unaccompanied girls who are particularly vulnerable to physical and sexual violence (6).

Migrant women have problems in accessing health services.

Access to health care is currently an issue in the whole of Africa, as many African countries don’t have adequate free public health care services even for their own citizens. The Sub-Saharan region scores the lowest in WHO Universal Health Coverage (UHC) service coverage index 2015 being 42% and the Northern Africa region has the fourth lowest coverage just marginally higher than the third lowest the South-Eastern Asia region (7). Africa has an estimated 88.1M people (10.3% of population) having to use out-of-pocket payments exceeding 10% of household’s total consumption or income (est. 2010) (7). Migrants face additional challenges when trying to access health care and thus may be less likely than other populations to fully benefit from their host country’s healthcare system.

Migrant women are sensitive to the more general barriers for migrants’ to access health care. Irregular migrants in particular are more vulnerable as they often have limited access to health services due to their fear of being discovered, detained and deported (2). Accessing optimal health services is also connected to issues of language, culture, knowledge, education, and cost.

Poor language skills are one of the most important barriers to access health services as it prevents migrants from understanding treatment instructions and from being able to communicate information about their health to practitioners (8). Necessary translated information, when available, is often not enough to address this barrier, as there is a low literacy level among many of the African migrant women (9). For example in South Africa, ‘"Somali women are facing a big problem at clinics, as some women are being sterilized without their consent: When our women go to maternity clinics they are abused and given family planning without their consent. Some of them find out that they can’t have kids anymore while they didn’t know when they had been sterilized. I think it is because many of them don’t know English and are forced to sign what they don’t understand" (24). Migrants might also not understand the differences between their origin country and the host country’s health systems (2). For instance, the former might have a stronger emphasis on curative services while the latter runs preventive health campaigns (10).

Yet, these genuine communication and knowledge difficulties don’t fully explain the lack of access to health treatment and xenophobic behaviours are also to blame. As Jonathan Crush and Godfrey Tawodzera analysed in a 2011 study in South Africa, medical practitioners often refuse to use a common language or to call for translators as a tactics to discriminate against Zimbabwean migrants seeking treatment (11).

Cultural and social norms and practices also have a major influence on African migrant women’s access to health care services. For instance, external stigmatisation or self-stigma around sexually transmitted infections such as HIV/AIDS or cultural practices, such as female genital mutilation or cutting, are a barrier to access related health services (12).

Last but not least, many migrants don’t have the economic means to afford mainstream health care services as they live in economic hardship, as a 2006 study by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) has shown (13). Again, this is particularly true for irregular migrants and sex workers who thus suffer from a double burden: their poor economic status prevents them from access private health care services while their irregular or unlawful status renders them unable to utilise free public health services (2).

What is the policy response?

Both origin and host countries have a responsibility to ensure the availability and accessibility of adequate health care facilities and services to all Africans without any form of discrimination or prejudice. Despite the development and ratification of numerous laws and international agreements recognising health as a fundamental human right for all and the promotion of the safety of women on the move (2) (3), the adoption of these mechanisms in practice is still far from optimal (2).

Most African countries don’t provide the same access to health care services to migrants and refugees as they do for their own citizens (2). More specifically for women and girls on the move, many countries leave out migrant women in ‘health promotion activities such as: immunization and vaccination, family planning campaigns, antenatal and safe delivery campaigns, as well as child nutrition campaigns including breast feeding’ (2).

Problems of misogyny, xenophobia, and racism must be addressed by migrant-sensitive health systems and awareness and sensitivity training on cultural and gender sensitivities for the health workforce (8). For instance, hospitals and clinics would be more accessible to migrants if they included direct and non-discriminatory translating services when accessing treatment (14). Prevention campaigns, such as the recent breast and cervical cancer prevention in October (15), must be inclusive of migrant women and shape around their specific needs. Best practices should be replicated like the inclusion of documented and undocumented asylum seekers and refugees specifically as recipients of healthcare provision by the State in South Africa, in terms of a 2007 Department of Health Directive (25).

There is also a need for more specific intersectional studies of migration as there is a lack of data and literature on patterns of access to health care for the various categories of female African migrants (2).

As WHO was warning us in 2018, “population mobility may hinder effective outbreak control and increases the risk of disease spreading across international borders” (2). The ongoing Covid-19 pandemic is a good example of this phenomenon. The spread of the virus in communities is highly correlated with poor living and work conditions. As we explained in our previous blog post of this series, migrant women are particularly affected by the Covid-19 restrictions and many have lost all sources of income, and are facing new challenges in accessing their own and their families’ basic needs, including nutrition and health (1).

Migration can be empowering for women as it gives them more autonomy, self-confidence, self-esteem, greater human capital, economic opportunities, skills and expertise, and helps them escape from oppressive gender and cultural norms and traditions, which can have a positive impact on their origin and host communities (16). Women may eventually resettle in their final destination where they engage in productive work, continue schooling, participate actively in the community as responsible citizens, and generally rebuild their lives while generating momentum for positive change within their home communities (2). Indeed, migrant women are sending a higher percentage of their income in remittances than men, and women left behind are more likely to receive remittances than other community members (17). In addition, host countries can capitalise on migrant women working in health care to create a ‘brain gain’, as shown by a South African initiative by the non-governmental organisation Africa Health Placements (AHP) (18). It is essential to take care of migrant women’s health in order for them to thrive in their communities and to create a more gender equal and inclusive Africa (19).

Keep an eye out for our following articles in the series addressing migrant women’s exclusion from social and education services!

James Chapman and Nolwenn Marconnet

SIHMA SIHMA

Project Manager Research and Communication Intern

Resources:

- SIHMA, 2020. The Exclusion of Migrant Women – Access to the Labour Market: https://sihma.org.za/Blog-on-the-move/the-exclusion-of-migrant-women-in-africa-access-to-the-labour-market

- WHO, 2018. Women on the move: migration and health In the WHO African Region: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/274378/9789290234128-eng.pdf

- WHO, 2018. Health of refugees and migrants Regional situation analysis, practices, experiences, lessons learned and ways forward WHO African Region 2018: https://www.who.int/migrants/publications/AFRO-report.pdf

- Human Rights Watch (HRW), 2016. “I Was Sold” Abuse and Exploitation of Migrant Domestic Workers in Oman: https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/07/13/i-was-sold/abuse-and-exploitation-migrant-domestic-workers-oman

- WHO, 2011. An Analysis of Migration Health in Kenya: https://www.who.int/hac/techguidance/health_of_migrants/analysis_of_migration_health_kenya.pdf

- UNFPA, 2006. Sexual Violence Against Women and Girls in War and Its Aftermath: Realities, Responses and Required Resources: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/CCEF504C15AB277E852571AB0071F7CE-UNFPA.pdf

- The World Bank, 2017. Tracking universal health coverage: 2017 global monitoring report: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259817/9789241513555-eng.pdf?sequence=1

- WHO, 2010. Health of migrants: the way forward - report of a global consultation, Madrid, Spain, 3-5 March 2010: https://www.who.int/hac/events/consultation_report_health_migrants_colour_web.pdf

- Ochieng, B.M., 2013, Black African Migrants: the barriers will accessing and utilizing health promotion services in the UK: https://academic.oup.com/eurpub/article/23/2/265/680894

- Ogunsiji, O.O., 2009. Meaning of Health: Migration Experience and Health Seeking Behaviour of West African Women in Australia: https://researchdirect.westernsydney.edu.au/islandora/object/uws:7065/

- Crush, J., Tawodzera, G., 2011. Medical xenophobia: Zimbabwean access to health services in South Africa: https://media.africaportal.org/documents/SAMP-_Medical_Xenophobia.pdf

- Zihindula, G., Meyer-Weitz, A., Akintola, O., 2015. Access to healthcare services by refugees in southern Africa: A review of literature: https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/soutafrijourdemo.16.1.7.pdf?casa_token=Ws_XeV35pXwAAAAA:D7T0VW3MawZktjomWLkPc_9C1jeKgSSyLm-QwTyVRrDK2SyZEtpFCAFm4Pj6DAEOQxmliPZ9DuuMJ2u1wnJjZr0kWUvWJrvzWiCcHm4vCAau9zEUrcFg

- IOM, 2006. Breaking the Cycle of vulnerabilities; responding to the health needs of trafficked women in East and Southern Africa: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/iom_breakingthecycleofvulnerability.pdf

- Mohamud, S M., et al., 2006. Barriers to access to health care for newly resettled sub-Saharan refugees in Australia: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00721.x

- Global Health Strategies, 2020. Breast and Cervical Cancer: A multi-stakeholder perspective on risks, prevention, screening and support: https://event.webinarjam.com/register/458/7vnora3m?utm_source=Webinarblast&utm_campaign=17d833c678-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2020_10_22_09_07&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_388b6df71c-17d833c678-331806414

- O'Niel T., Fleury A., Foresti, M., 2016. Women on the move: Migration, gender equality and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC): https://doc.rero.ch/record/308979/files/22-12._ODI_Women.pdf

- UN Women, 2013. Gender on the Move: Working on the Migration-Development Nexus from a Gender Perspective: https://www.sdgfund.org/gender-move-working-migration-development-nexus-gender-perspective

- African Institute for Health and Leadership Development, 2017. From Brain Drain to Brain Gain: Understanding and Managing the Movement of Medical Doctors in the South African Health System: https://www.who.int/workforcealliance/brain-drain-brain-gain/17-304-south-africa-case-studies2017-09-26-justified.pdf

- The Daily Vox, 2020. The fight against sexism and GBV must include migrant, refugee women: https://www.thedailyvox.co.za/the-fight-against-sexism-and-gbv-must-include-migrant-refugee-women/

- The Globe and Mail, Thousands of migrants head back to Ethiopia after deportations as pandemic sparks fears: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/world/article-thousands-of-migrants-head-back-to-ethiopia-after-deportations-as/

- Reuters, U.N. says Saudi deportations of Ethiopian migrants risks spreading coronavirus https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-ethiopia-migrants-idUSKCN21V1OT

- Human rights Watch, Immigration Dentations in Saudi Arabia During Covid-19: https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/10/19/immigration-detention-saudi-arabia-during-covid-19

- Amnesty international https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/10/ethiopian-migrants-hellish-detention-in-saudi-arabia/

- A. Rachid, October 2015 referenced in AHMR Journal, Turning a Blind Eye to African Refugees and Immigrants in a Tourist City: A Case-study of Blame-shifting in Cape Town: https://sihma.org.za/journals/AHMR%206:1%20-%2002%20Turning%20a%20Blind%20Eye%20to%20African%20Refugees%20and%20Immigrants%20in%20a%20Tourist%20City.pdf

- Scalabrini Centre of Cape Town, Migrant and Refugee Access to Public Healthcare in South Africa: https://scalabrini.org.za/news/migrant-and-refugee-access-to-public-healthcare-in-south-africa/ and http://www.probono.org.za/Downloads/asylum_seekers.pdf

Categories:

Tags: